All objects are in the collection of the Geoffrey Bawa Trust, unless otherwise noted. Every effort has been taken to ensure the veracity of the information provided, however the process of identifying and learning about the material in the archive is an ongoing and continual process. Please contact us at archive@gbtrust.net with any additional information or corrections. All content is copyright to the Geoffrey Bawa Trust and the authors of the works displayed, all rights reserved.

Introduction

Geoffrey Bawa’s distinct practice as an architect began with the purchase of an abandoned rubber and cinnamon estate, which he would transform into the garden that is now Lunuganga, in 1948, in the wake of the country’s newly gained independence from the British Empire. From this very first work, the practice is marked by architecture that seeks to understand the notion of place.

In a practice so attuned to the generative aspects of place, drawings play a complex role. Part process, part record, the drawings were often a vehicle for the ideas about a place. In retrospect, the drawings offer clues to these ideas, and suggest additional readings of the ways in which the practice grappled with its spatial and temporal context.

Although Bawa’s work has been exhibited at multiple venues in the UK, USA, Australia, India, Brazil, Singapore, and Germany, this is the first exhibition of Bawa’s work in Sri Lanka.

In a practice so attuned to the generative aspects of place, drawings play a complex role. Part process, part record, the drawings were often a vehicle for the ideas about a place. In retrospect, the drawings offer clues to these ideas, and suggest additional readings of the ways in which the practice grappled with its spatial and temporal context.

Although Bawa’s work has been exhibited at multiple venues in the UK, USA, Australia, India, Brazil, Singapore, and Germany, this is the first exhibition of Bawa’s work in Sri Lanka.

“I like to regard all past and present good architecture in Sri Lanka as just that — good Sri Lankan architecture — for this is what it is, not narrowly classified as Indian, Portuguese or Dutch, early Sinhalese or Kandyan or British Colonial, for all the good examples of these periods have taken the country itself into first account.”

Clara Kraft Isono

Geoffrey Bawa Documentary: Lunuganga arrival montage, due for release late 2022

Single channel video, 0:43 seconds

Courtesy of the artist

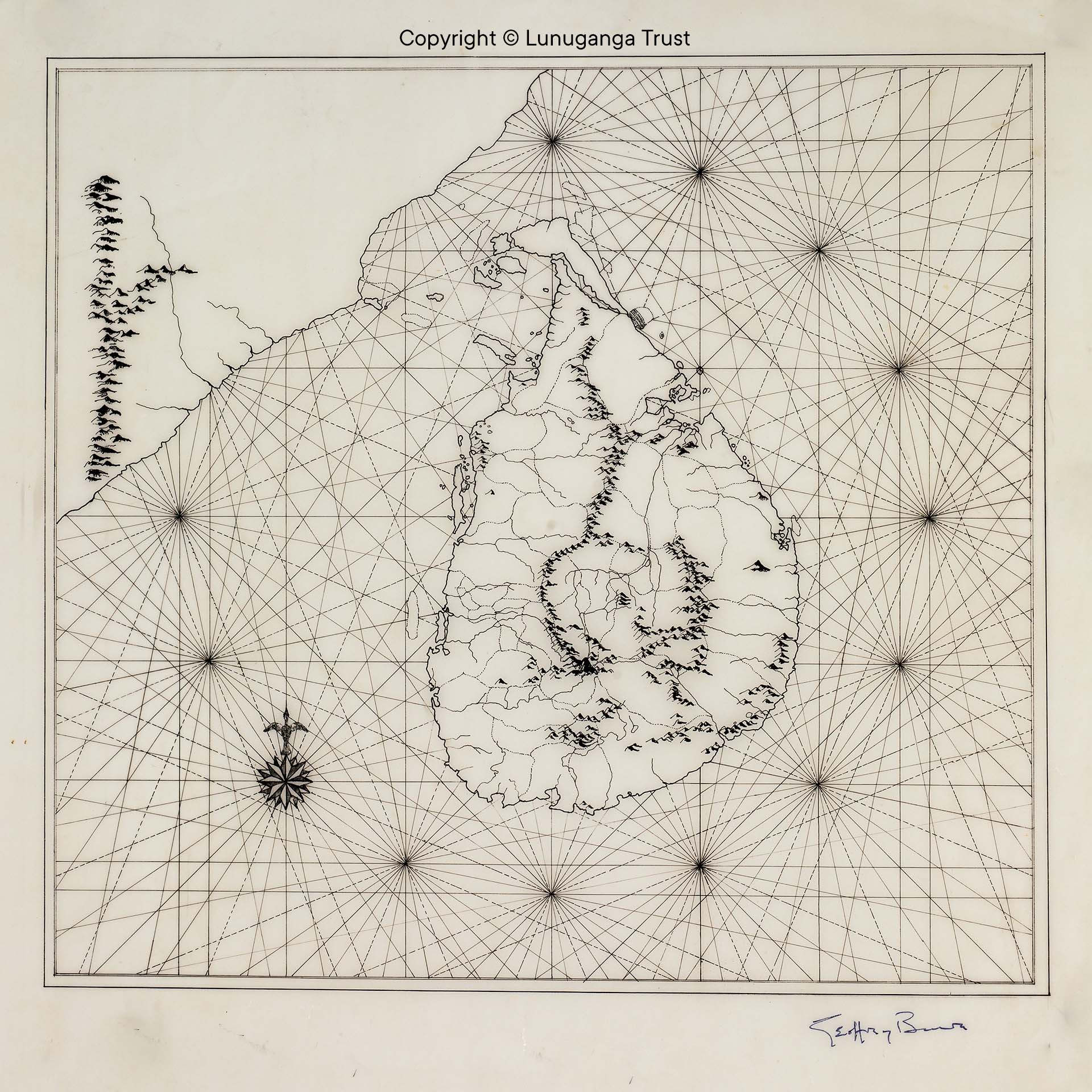

Author unknown

Map of the World Centred on Colombo, c. 1985

Author unknown

Map of Sri Lanka c. 1985

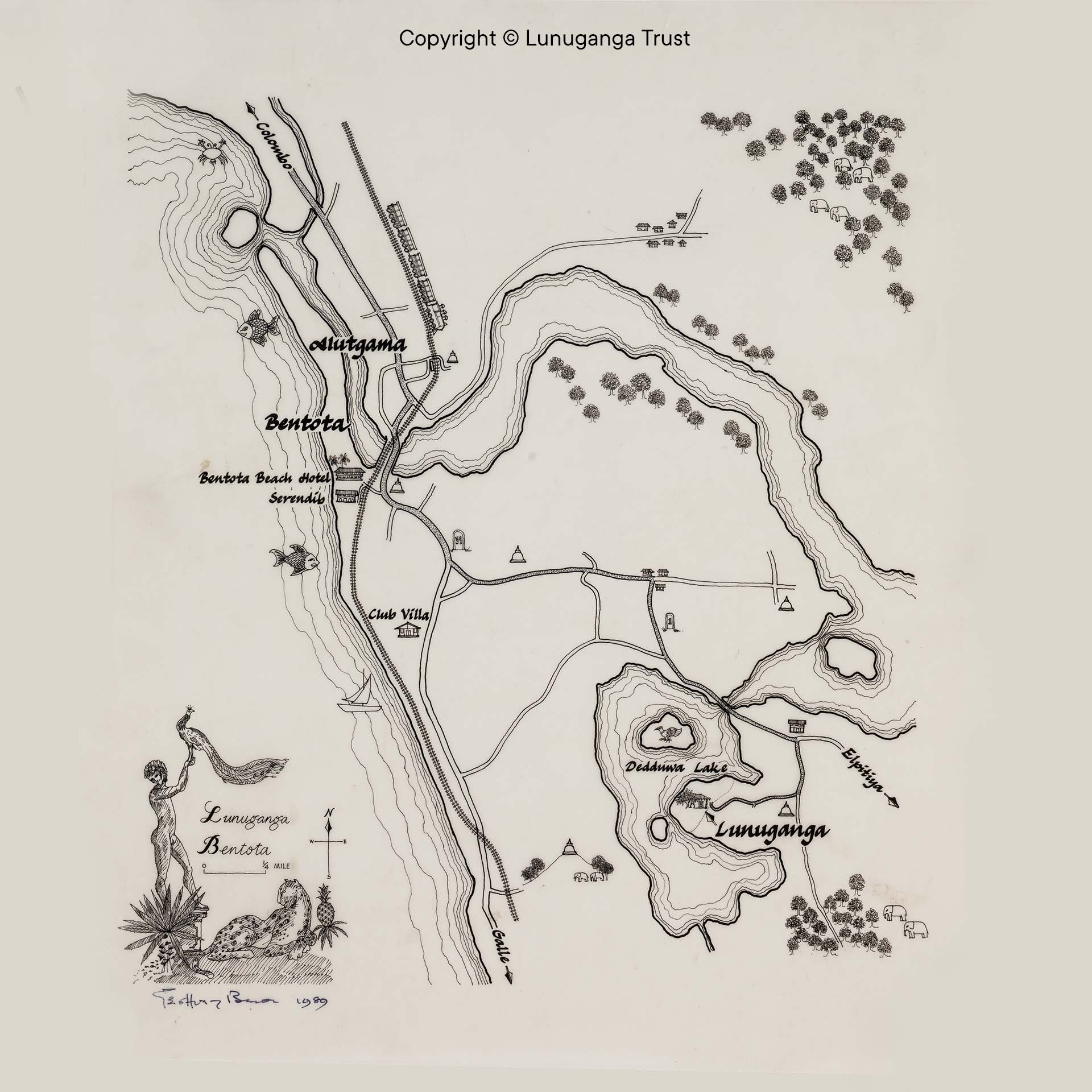

Sumangala Jayatillaka

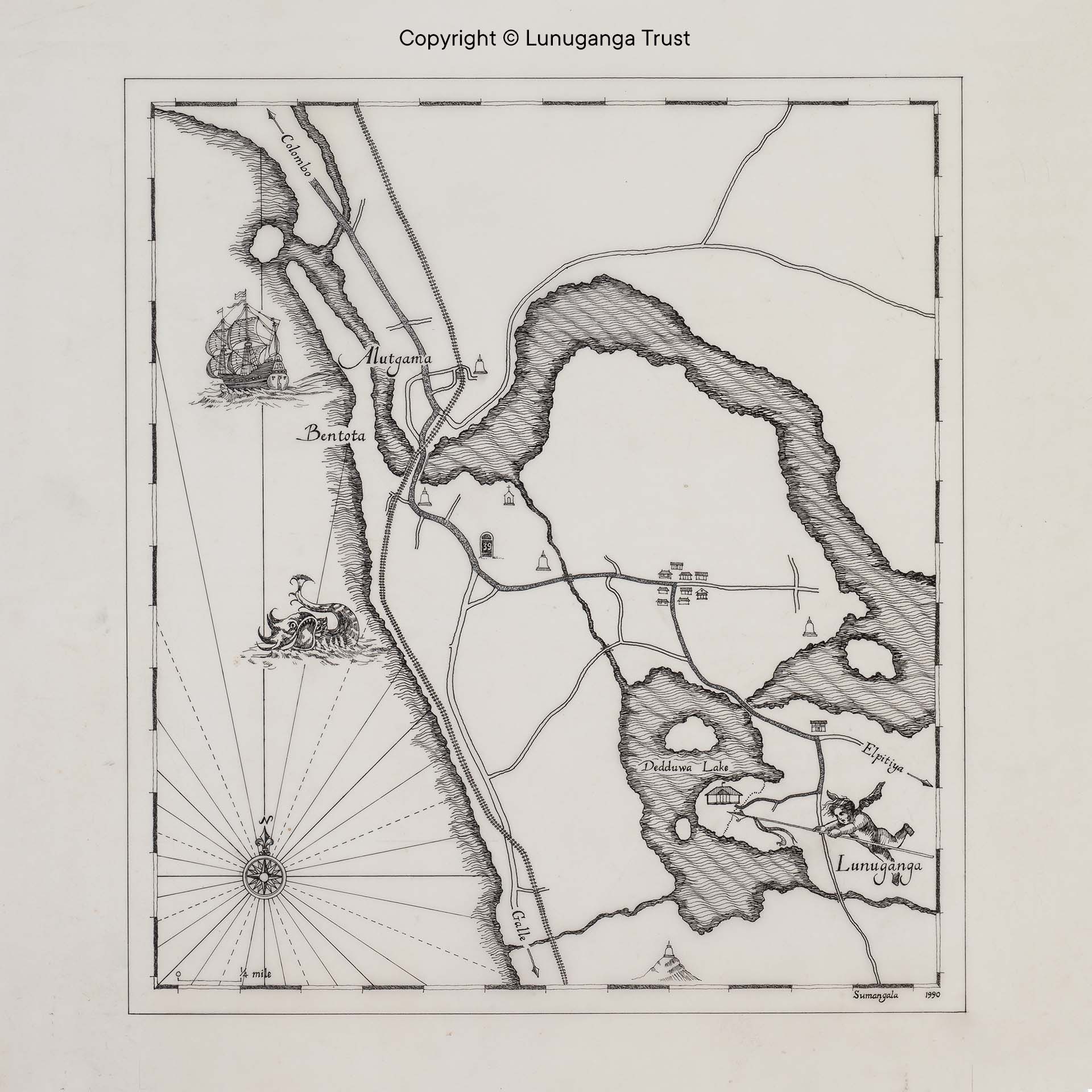

Lunuganga Map, 1990

Sumangala Jayatillaka

Lunuganga Map, c. 1987–1990

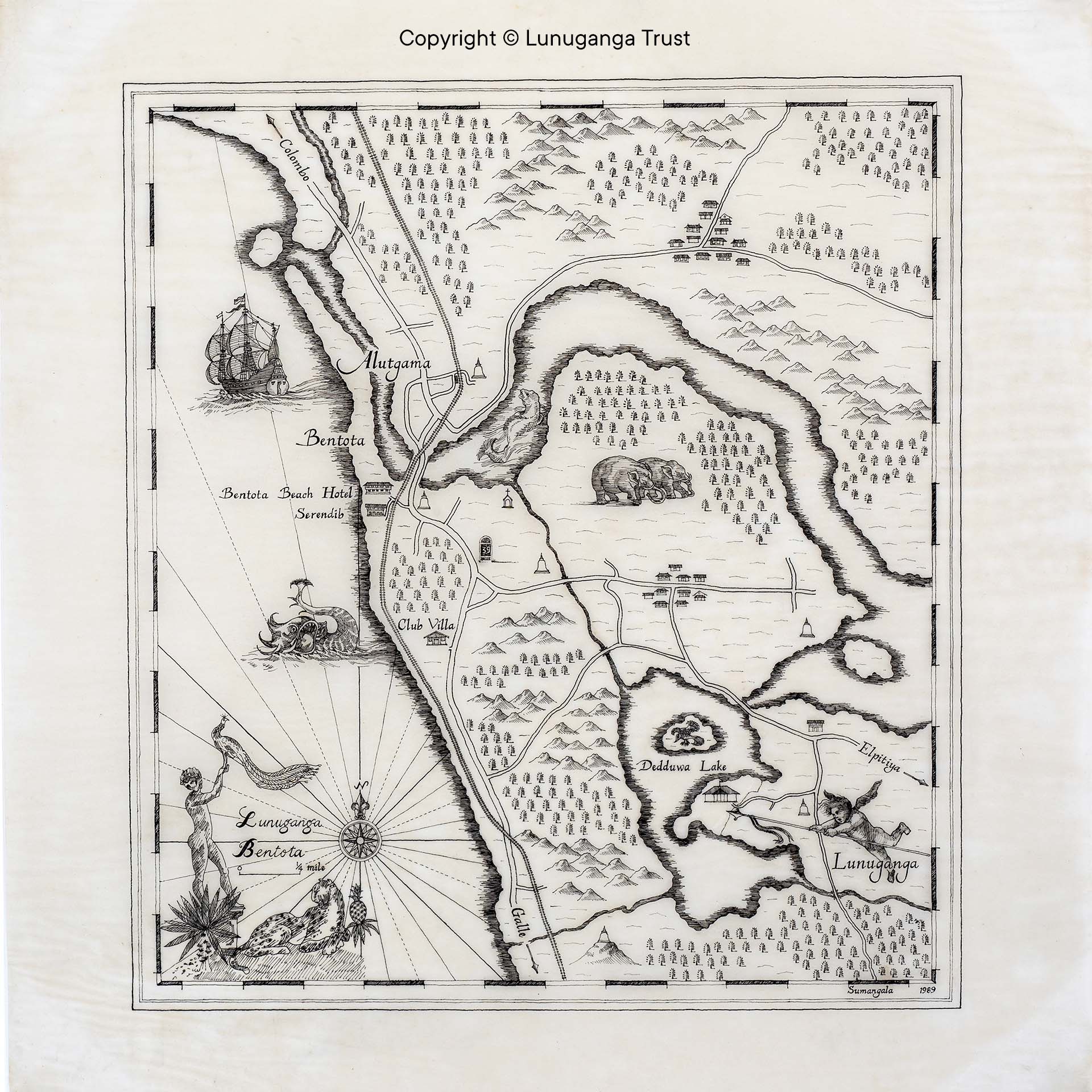

Sumangala Jayatillaka

Lunuganga Map, 1989

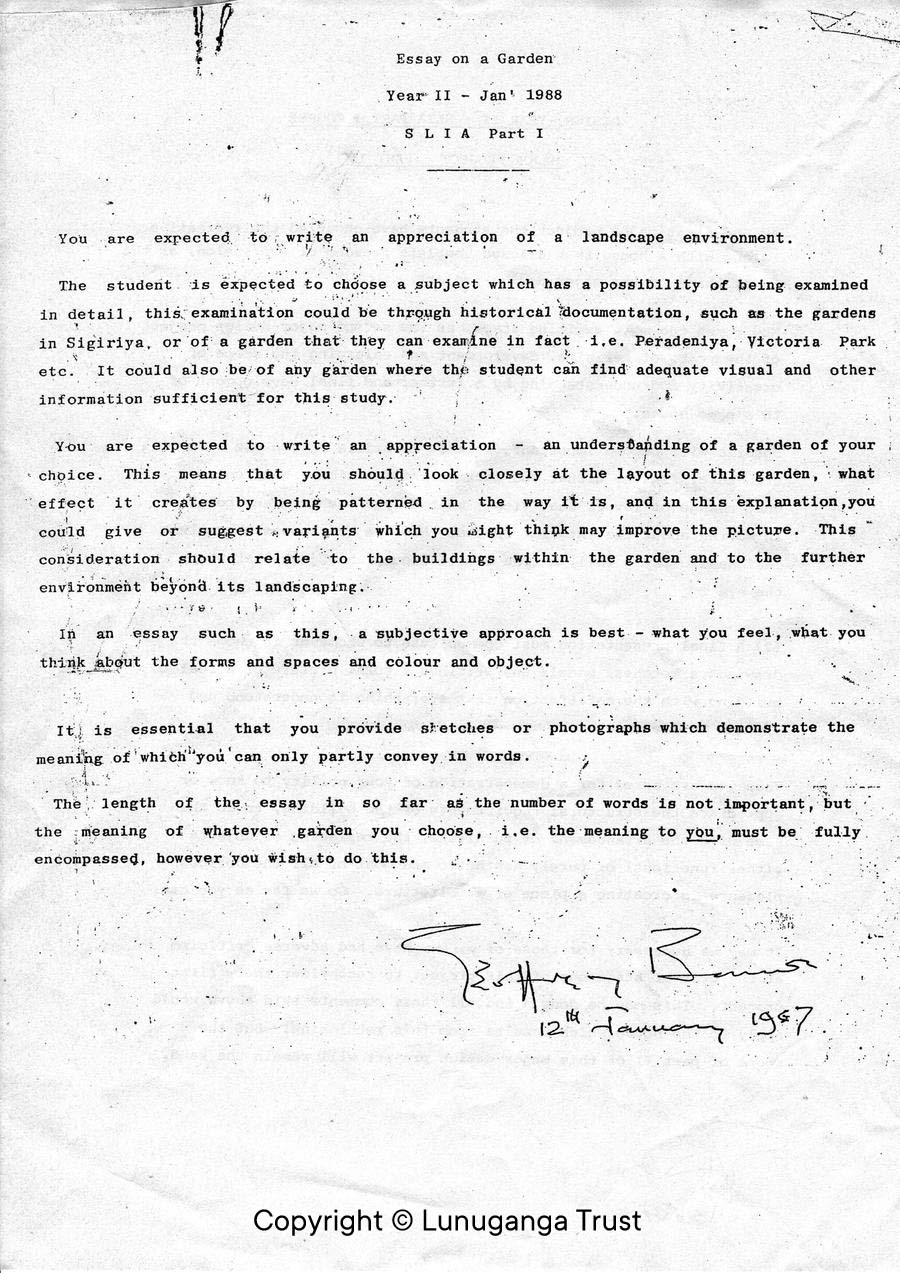

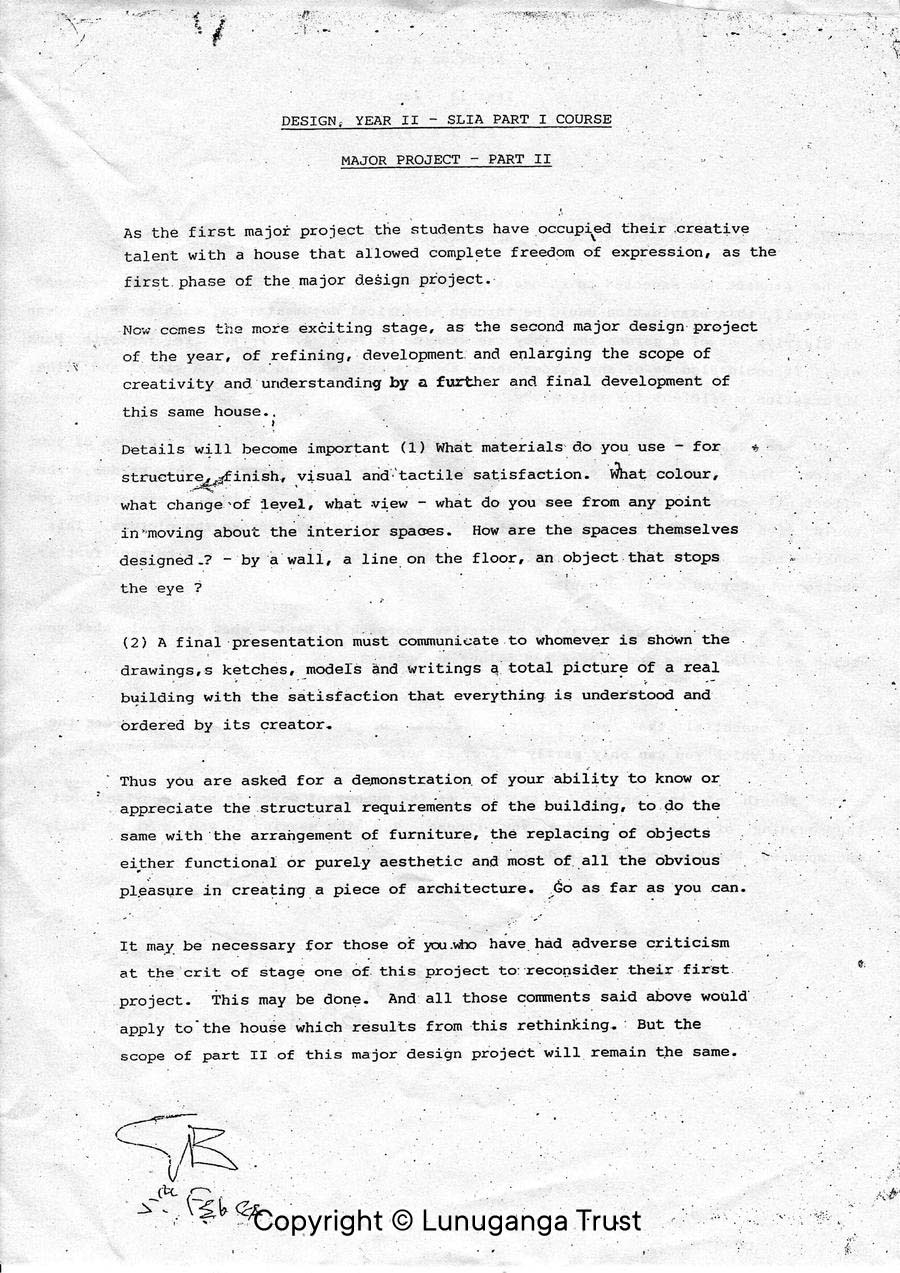

Geoffrey Bawa

Two-part assignment for Part I students at the Sri Lanka Institute of Architects, 1988

Two-part assignment for Part I students at the Sri Lanka Institute of Architects, 1988

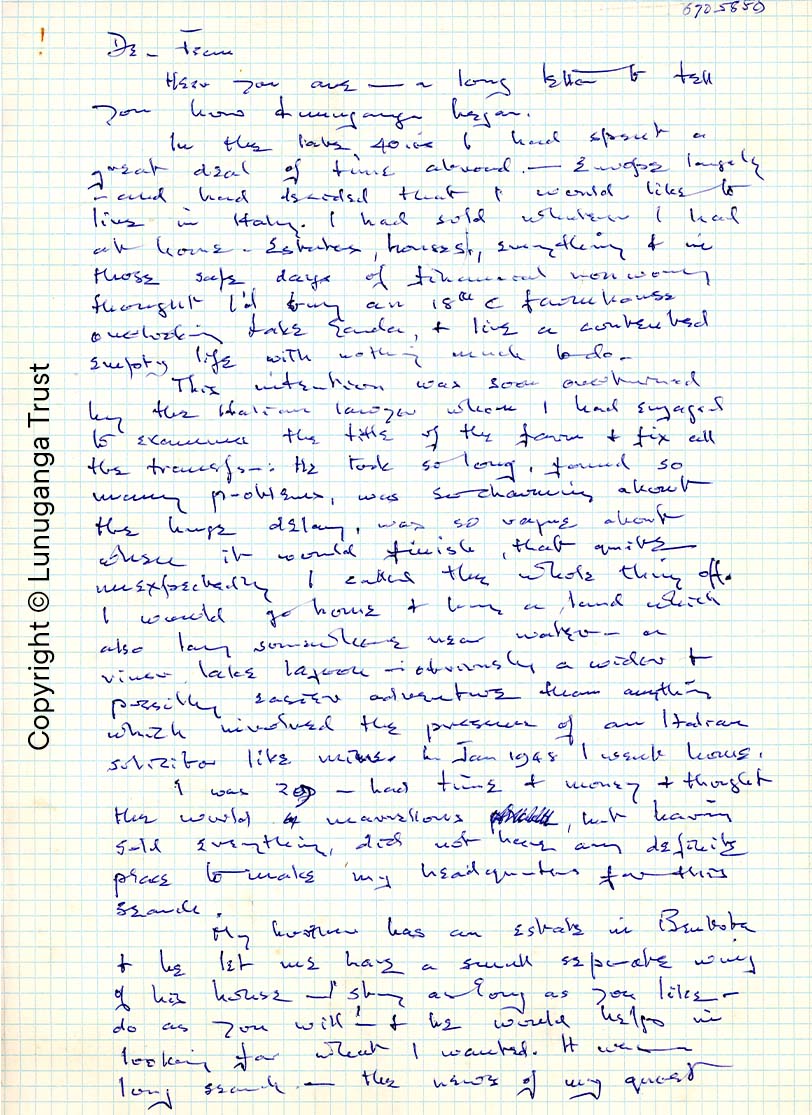

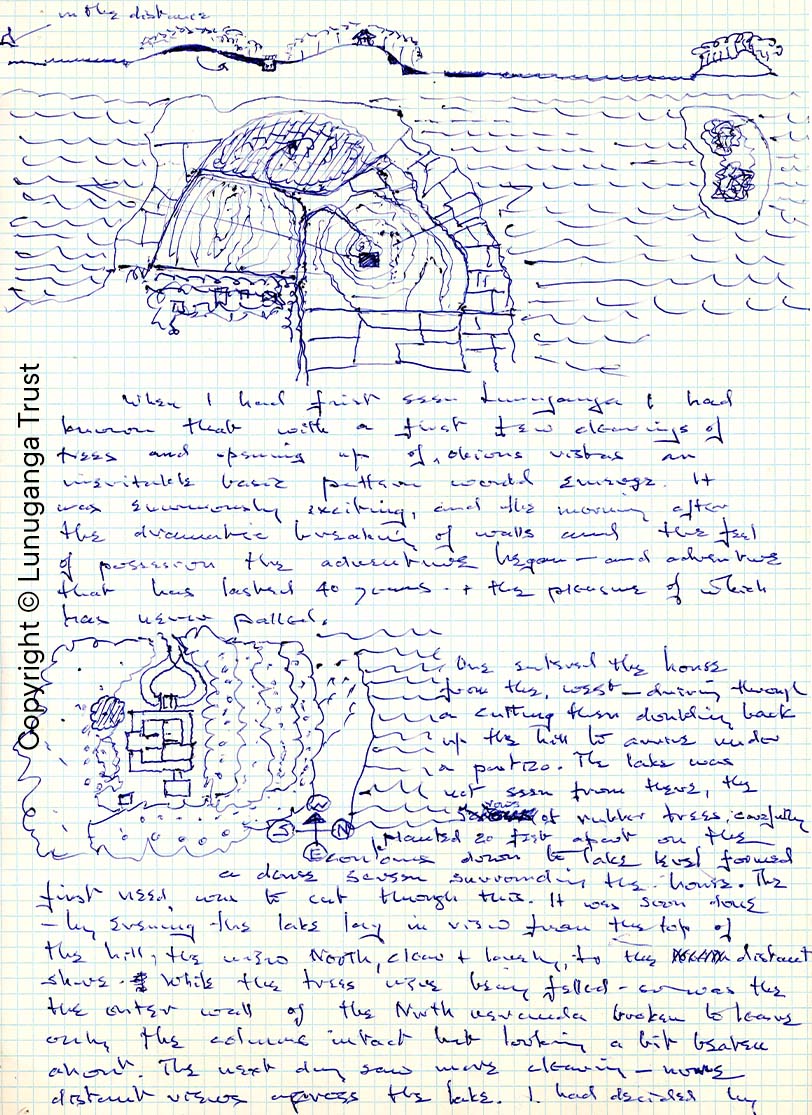

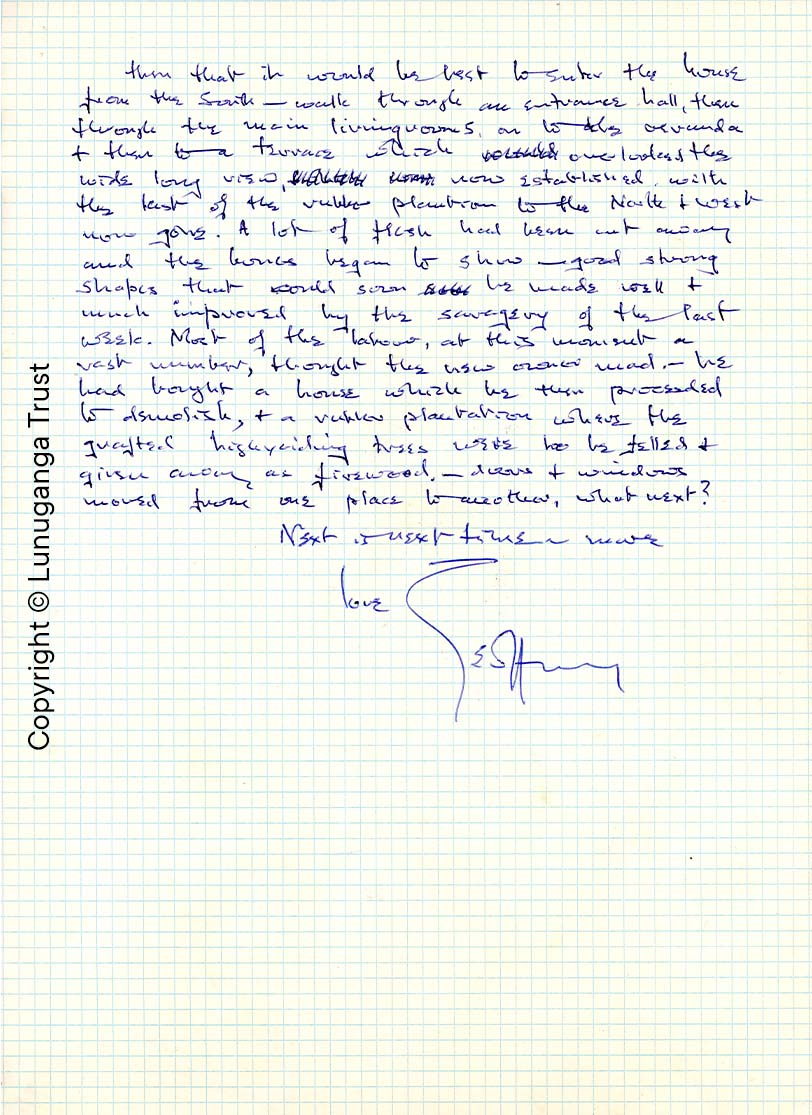

This letter to Bawa’s friend, Jean Chamberlin, describes finding an abandoned rubber and cinnamon estate and the project of transforming it into what would become the garden of Lunuganga. Bawa’s emphasis on moving home, on the eve of the island’s independence from the British Empire, is noteworthy, as are the sketches he uses where words are insufficient to describe his process.

Geoffrey Bawa

Letter to Jean describing the origins of Lunuganga, c. 1986

Ink on square ruled paper

Gift of Jean Chamberlin

This letter to Bawa’s friend, Jean Chamberlin, describes finding an abandoned rubber and cinnamon estate and the project of transforming it into what would become the garden of Lunuganga. Bawa’s emphasis on moving home, on the eve of the island’s independence from the British Empire, is noteworthy, as are the sketches he uses where words are insufficient to describe his process.

Dear Jean,

Here you are– a long letter to tell you how Lunuganga began.

In the late 40s I had spent a great deal of time abroad– Europe largely– and had decided that I would like to live in Italy. I had sold whatever I had at home– estates, houses, everything and in those safe days of financial non worry thought I’d buy an 18th c farmhouse overlooking Lake Garda, and live a contented empty life with nothing much to do.

This intention was soon overwhelmed by the Italian lawyer whom I had engaged to examine the title of the farm and fix all the [transfers]. He took so long, found so many problems, was so charming about the huge delay, was so vague about when it would finish, that quite unexpectedly I called the whole thing off. I would go home and buy a land which also lay somewhere near water– a river lake lagoon– obviously a wider and possibly easier adventure than anything which involved the presence of an Italian solicitor like mine. In Jan 1948 I went home.

I was 29– had time and money and thought the world marvellous, but having sold everything, did not have any definite place to make my headquarters for this search.

My brother has an estate in Bentota and he let me have a small private wing of his house– ‘stay as long as you like– do as you will’– and he would help in looking for what I wanted. It was a long search– the news of my quest

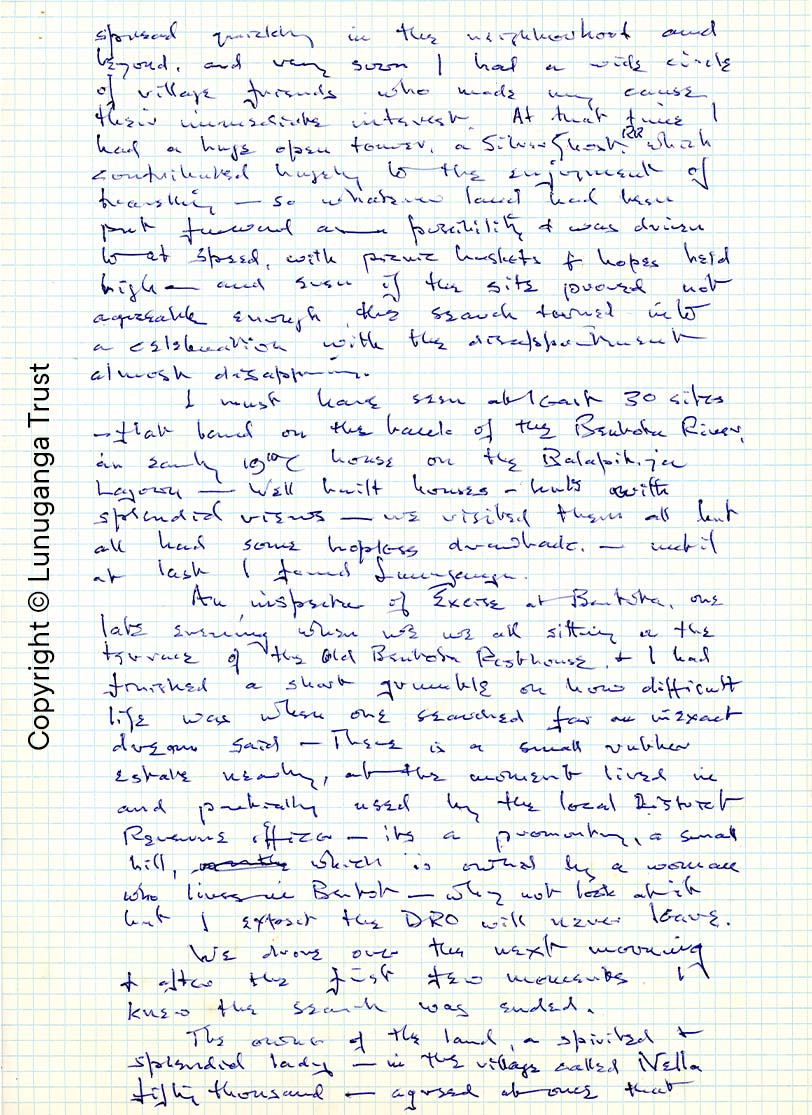

PAGE 2

spread quickly in the neighbourhood and beyond, and very soon I had a wide circle of village friends who made my cause their immediate interest. At that time I had a huge open tourer, a Silver Ghost RR which contributed hugely to the enjoyment of travelling– so whatever land had been put forward as a possibility was driven to at speed, with picnic baskets and hopes held high– and even if the sites proved not acceptable enough, the search turned into a celebration with the disappointment almost disappearing.

I must have seen almost 30 sites– flat land on the banks of the Bentota River, an early 19th c house on the Balapitiya Lagoon– well built houses– huts with splendid views– we visited them all but all had some hopeless drawback– when at last I found Lunuganga.

An inspector of Excise at Bentota, one late evening when we were all sitting in the terrace of the Old Bentota Resthouse, and I had finished a short grumble on how difficult life was when one searched for an exact dream said– There is a small rubber estate nearby, at the moment lived in and partially used by the local District Revenue Officer– it’s a promontory, a small hill, which is owned by a woman who lives in Bentota– why not look at it but I expect the DRO will never leave.

We drove over the next morning and after the first few moments I knew the search was ended.

The owner of the land, a spirited and splendid lady– in the village called Nella fifty thousand– agreed at

PAGE 3

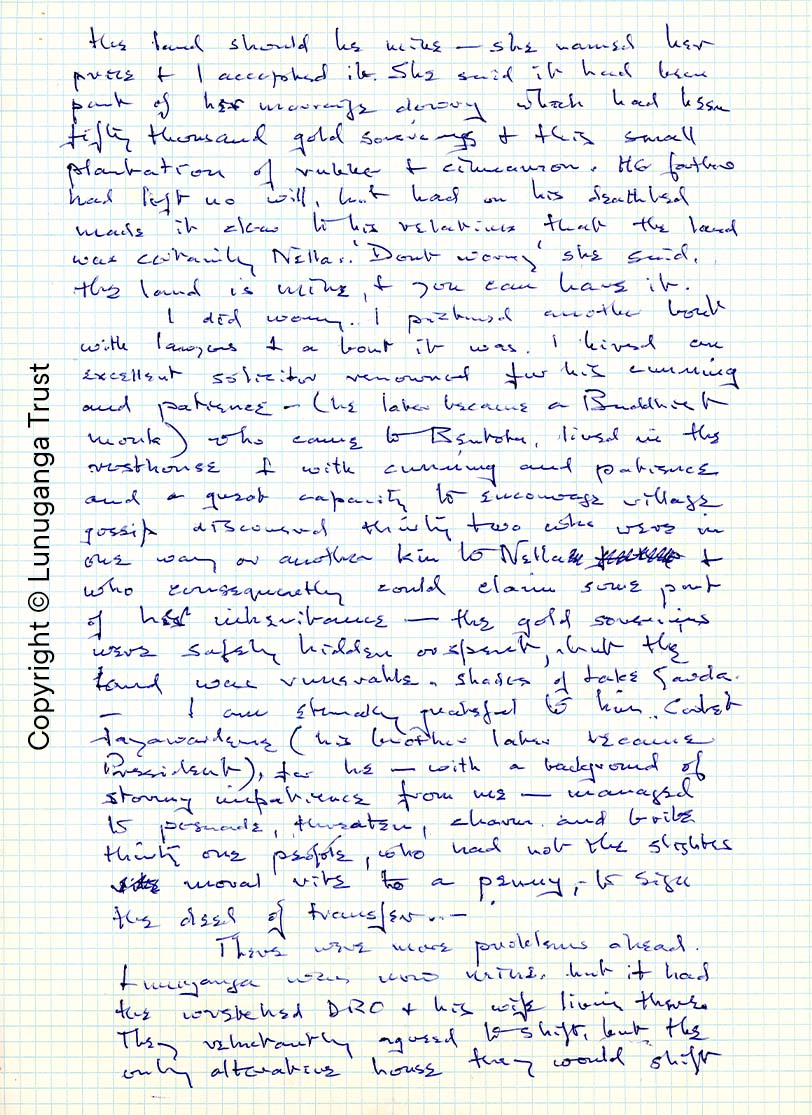

this land should be mine–she named her price and I accepted it. She said it had been part of her marriage dowry which had been fifty thousand gold sovereigns and this small plantation of rubber and cinnamon. Her father had left no will, but had on his deathbed made it clear to his relatives that the land was certainly Nella’s. ‘Don’t worry’ she said, the land is mine and you can have it.

I did worry. I pictured another bout with lawyers and a bout it was. I hired an excellent solicitor renowned for his cunning and patience (he later became a Buddhist monk) who came to Bentota, lived in the resthouse and with cunning and patience and a great capacity to encourage village gossip discovered thirty two who were in one way or another kin to Nella and who consequently could claim some part of her inheritance– the gold sovereigns were safely hidden [apart], but the land was vulnerable, shades of Lake Garda.

I am eternally grateful to him Corbert Jayawardene (his brother later became President), for he– with a background of stormy impatience from me – managed to persuade, threaten, [-] and bribe thirty one people, who had not the slightest moral rite to a penny, to sign the deed of transfer.

There were more problems ahead. Lunuganga was now mine, but it had the [-] DRO and his wife living there. They reluctantly agreed to shift, but the only alternative house they would shift

PAGE 4

to was occupied by the Excise commissions office. So they had to move and then only when the house occupied by the village schoolmaster was available– so the schoolmaster had to move and he would only do so if I built him a sizable addition to his brother’s house nearby. All this was agreed to, promises made and kept, except by the initial mover of these moves– the villanous DRO, who on the promised day of his departure said that he would move but only when he came back from his annual leave which he had now decided to take before the trauma of house moving. We said yes, yes do, by all means, but when the dim tail light of his Hillman Minx vanished down the road we summoned an already arranged, prepared gang of masons, carpenters and a large number of villagers and broke down the outer walls of the veranda. Patient no more we enjoyed the evening –we built a shed on a cleared patch of land between the rubber trees, moved all the furniture into it and locked the door. The house was empty – a free wind swept through it. It had been won in battle – a rather unfair warlike move but exciting and wholly permissible. Nothing had been broken except for DROs promise and the walls of his erstwhile house, and the land of Lunuganga was mine so I could begin to mould it into something that would be shaped by my present and future dreams and imaginings.

PAGE 5

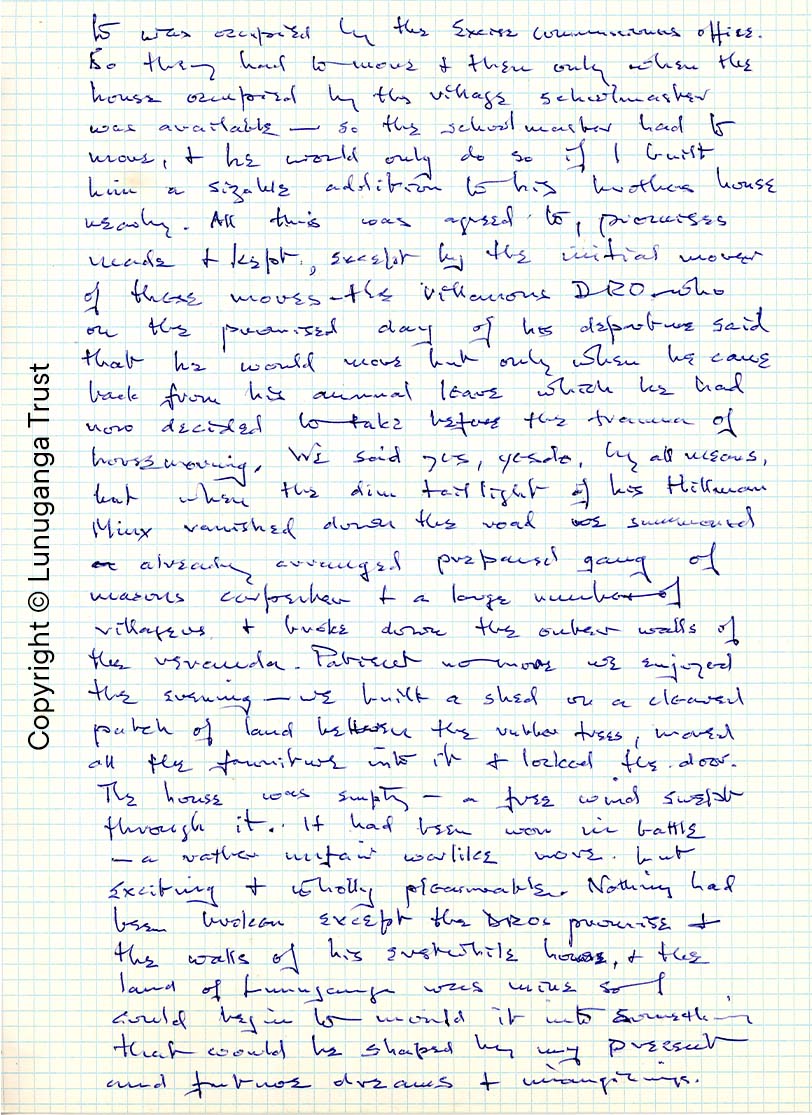

When I had first seen Lunuganga I had known that with a first few clearings of trees and opening up of [-] vistas an inevitable basic pattern would emerge. It was enormously exciting, and the morning after the dramatic breaking of walls and the feel of possession the adventure began– and adventure that has lasted 40 years and the pleasure of which has never paled.

One entered the house from the west–driving through a cutting then doubling back up the hill to arrive under a portico. The lake was not seen from there, the rows of rubber trees, carefully planted 20 feet apart on the contours down to lake [-] formed a dense screen surrounding the house. The first need was to cut through this. It was soon done– by evening the lake lay in view from the top of the hill, the view North, clear and lovely, to the distant shore. While the trees were being felled– so was the outer wall of the North veranda broken to leave only the columns intact but looking a bit [-] about. The next day saw more clearing– more distant views across the lake. I had decided by

PAGE 6

then that it would be best to enter the house from the south– walk through an entrance hall, then through the main living rooms on to the veranda and then to a terrace which overlooked the wide long view now established, with the last of the rubber plantation to the north and west now gone. A lot of flesh had been cut away and the bones began to show – good strong shapes that would soon be made well and much improved by the savagery of the last week. Most of the labour, at this moment a vast number, thought the new owner mad– he had bought a house which he then proceeded to demolish, and a rubber plantation where the grafted high–yielding trees were to be felled and given away as firewood– doors and windows moved from one place to another, what next?

Next is next time’s news.

love,

Geoffrey

Dear Jean,

Here you are– a long letter to tell you how Lunuganga began.

In the late 40s I had spent a great deal of time abroad– Europe largely– and had decided that I would like to live in Italy. I had sold whatever I had at home– estates, houses, everything and in those safe days of financial non worry thought I’d buy an 18th c farmhouse overlooking Lake Garda, and live a contented empty life with nothing much to do.

This intention was soon overwhelmed by the Italian lawyer whom I had engaged to examine the title of the farm and fix all the [transfers]. He took so long, found so many problems, was so charming about the huge delay, was so vague about when it would finish, that quite unexpectedly I called the whole thing off. I would go home and buy a land which also lay somewhere near water– a river lake lagoon– obviously a wider and possibly easier adventure than anything which involved the presence of an Italian solicitor like mine. In Jan 1948 I went home.

I was 29– had time and money and thought the world marvellous, but having sold everything, did not have any definite place to make my headquarters for this search.

My brother has an estate in Bentota and he let me have a small private wing of his house– ‘stay as long as you like– do as you will’– and he would help in looking for what I wanted. It was a long search– the news of my quest

PAGE 2

spread quickly in the neighbourhood and beyond, and very soon I had a wide circle of village friends who made my cause their immediate interest. At that time I had a huge open tourer, a Silver Ghost RR which contributed hugely to the enjoyment of travelling– so whatever land had been put forward as a possibility was driven to at speed, with picnic baskets and hopes held high– and even if the sites proved not acceptable enough, the search turned into a celebration with the disappointment almost disappearing.

I must have seen almost 30 sites– flat land on the banks of the Bentota River, an early 19th c house on the Balapitiya Lagoon– well built houses– huts with splendid views– we visited them all but all had some hopeless drawback– when at last I found Lunuganga.

An inspector of Excise at Bentota, one late evening when we were all sitting in the terrace of the Old Bentota Resthouse, and I had finished a short grumble on how difficult life was when one searched for an exact dream said– There is a small rubber estate nearby, at the moment lived in and partially used by the local District Revenue Officer– it’s a promontory, a small hill, which is owned by a woman who lives in Bentota– why not look at it but I expect the DRO will never leave.

We drove over the next morning and after the first few moments I knew the search was ended.

The owner of the land, a spirited and splendid lady– in the village called Nella fifty thousand– agreed at

PAGE 3

this land should be mine–she named her price and I accepted it. She said it had been part of her marriage dowry which had been fifty thousand gold sovereigns and this small plantation of rubber and cinnamon. Her father had left no will, but had on his deathbed made it clear to his relatives that the land was certainly Nella’s. ‘Don’t worry’ she said, the land is mine and you can have it.

I did worry. I pictured another bout with lawyers and a bout it was. I hired an excellent solicitor renowned for his cunning and patience (he later became a Buddhist monk) who came to Bentota, lived in the resthouse and with cunning and patience and a great capacity to encourage village gossip discovered thirty two who were in one way or another kin to Nella and who consequently could claim some part of her inheritance– the gold sovereigns were safely hidden [apart], but the land was vulnerable, shades of Lake Garda.

I am eternally grateful to him Corbert Jayawardene (his brother later became President), for he– with a background of stormy impatience from me – managed to persuade, threaten, [-] and bribe thirty one people, who had not the slightest moral rite to a penny, to sign the deed of transfer.

There were more problems ahead. Lunuganga was now mine, but it had the [-] DRO and his wife living there. They reluctantly agreed to shift, but the only alternative house they would shift

PAGE 4

to was occupied by the Excise commissions office. So they had to move and then only when the house occupied by the village schoolmaster was available– so the schoolmaster had to move and he would only do so if I built him a sizable addition to his brother’s house nearby. All this was agreed to, promises made and kept, except by the initial mover of these moves– the villanous DRO, who on the promised day of his departure said that he would move but only when he came back from his annual leave which he had now decided to take before the trauma of house moving. We said yes, yes do, by all means, but when the dim tail light of his Hillman Minx vanished down the road we summoned an already arranged, prepared gang of masons, carpenters and a large number of villagers and broke down the outer walls of the veranda. Patient no more we enjoyed the evening –we built a shed on a cleared patch of land between the rubber trees, moved all the furniture into it and locked the door. The house was empty – a free wind swept through it. It had been won in battle – a rather unfair warlike move but exciting and wholly permissible. Nothing had been broken except for DROs promise and the walls of his erstwhile house, and the land of Lunuganga was mine so I could begin to mould it into something that would be shaped by my present and future dreams and imaginings.

PAGE 5

When I had first seen Lunuganga I had known that with a first few clearings of trees and opening up of [-] vistas an inevitable basic pattern would emerge. It was enormously exciting, and the morning after the dramatic breaking of walls and the feel of possession the adventure began– and adventure that has lasted 40 years and the pleasure of which has never paled.

One entered the house from the west–driving through a cutting then doubling back up the hill to arrive under a portico. The lake was not seen from there, the rows of rubber trees, carefully planted 20 feet apart on the contours down to lake [-] formed a dense screen surrounding the house. The first need was to cut through this. It was soon done– by evening the lake lay in view from the top of the hill, the view North, clear and lovely, to the distant shore. While the trees were being felled– so was the outer wall of the North veranda broken to leave only the columns intact but looking a bit [-] about. The next day saw more clearing– more distant views across the lake. I had decided by

PAGE 6

then that it would be best to enter the house from the south– walk through an entrance hall, then through the main living rooms on to the veranda and then to a terrace which overlooked the wide long view now established, with the last of the rubber plantation to the north and west now gone. A lot of flesh had been cut away and the bones began to show – good strong shapes that would soon be made well and much improved by the savagery of the last week. Most of the labour, at this moment a vast number, thought the new owner mad– he had bought a house which he then proceeded to demolish, and a rubber plantation where the grafted high–yielding trees were to be felled and given away as firewood– doors and windows moved from one place to another, what next?

Next is next time’s news.

love,

Geoffrey