All objects are in the collection of the Geoffrey Bawa Trust, unless otherwise noted. Every effort has been taken to ensure the veracity of the information provided, however the process of identifying and learning about the material in the archive is an ongoing and continual process. Please contact us at archive@gbtrust.net with any additional information or corrections. All content is copyright to the Geoffrey Bawa Trust and the authors of the works displayed, all rights reserved.

Searching for a Way of Building

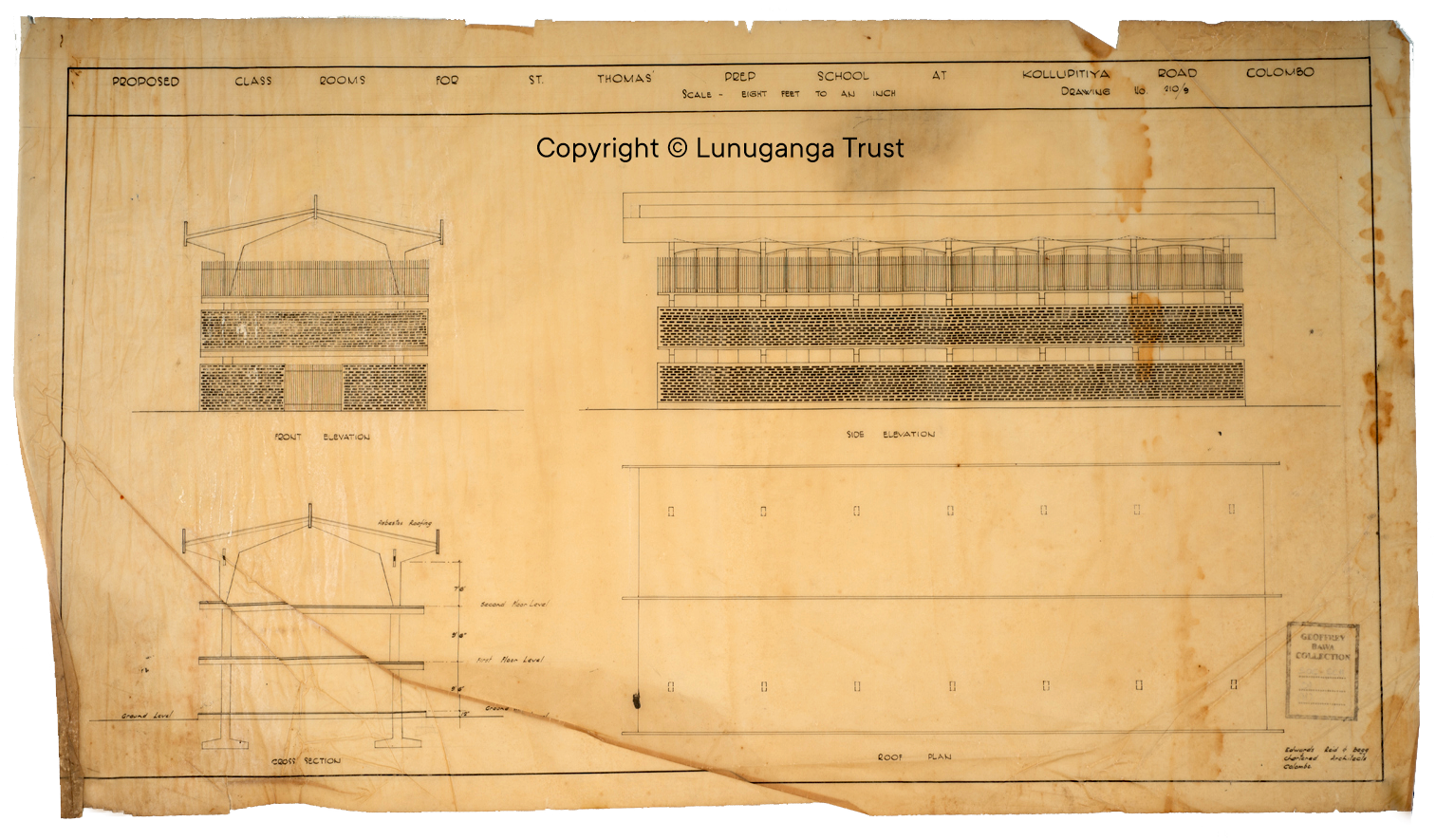

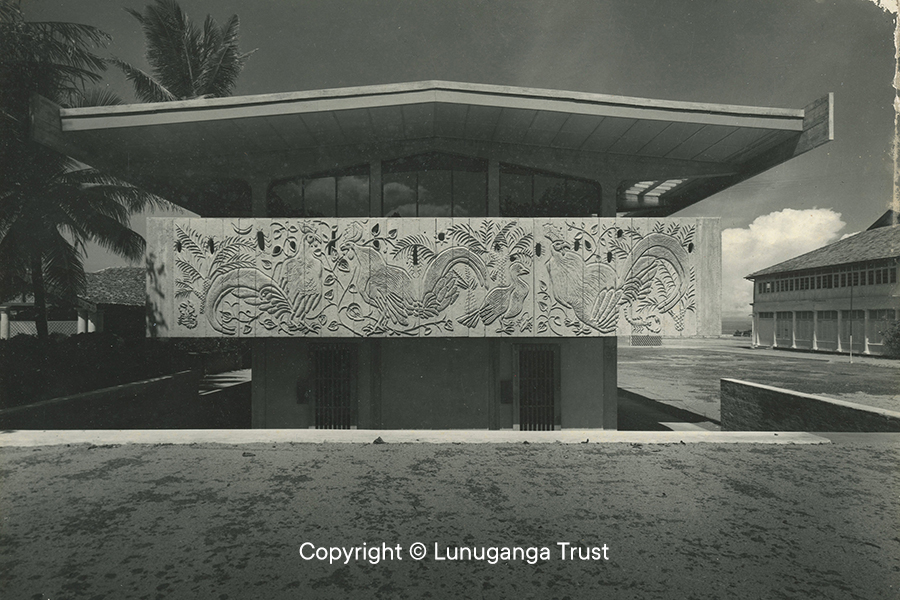

When Bawa formally began his architecture career as a partner at Edwards, Reid and Begg in 1957, the practice was inspired with the possibilities for innovation unlocked by the technological advancements of the Industrial Age. However, these options were soon cut short with Sri Lanka’s closed economy and ensuing austerity measures in the 1960s, which continued until 1977. Reinforced steel and glass — two materials that had liberated the architecture of the age — were in short supply in Sri Lanka. Bawa and his associates were left to find alternative means to express the forms and spaces they were conceiving of, using the materials at hand. At the same time, they began to explore the materials and methods of building from a pragmatic standpoint. The steel reinforcements that held up St. Thomas’ Preparatory School (1958–1962) corroded and the unsuitability of steel to the island’s climate soon became apparent. While St. Bridgets’ Montessori (1963–1964) is ostensibly still made of exposed concrete, the introduction of a monitor roof explored how the design of a building could better serve the Sri Lankan climate. This exploration of climatically-suited architecture is continued at Ladies’ College, in the evolution of the overhanging balconies at Simon Block, which offer shade to the floors below and ventilation through the classrooms, and also in the buttressed supports at the Steel Corporation Building. These innovations are refined in the remarkable roof-hung floor plate at the Bentota Beach Hotel. While the Hotel draws from familiar forms in Sri Lanka’s architecture, its structure is impressively innovative. The twelve-storey State Mortgage Bank Building (later known as the Mahaweli Building) is an extraordinary effort to construct an office building which can be naturally ventilated. Although it has been much altered today, it remains an important model for bioclimatically-responsive tall buildings.

“Although the past gives lessons, it does not give the whole answer to what must be done now. It is true that many materials available to us are the same as in the past. Their use, if sensible and right, is very alike, except where new techniques have added or changed their qualities. But with these materials, and, in addition, reinforced concrete and steel, we must now design for a much changed society living in a framework or a difficult economy — a faster life, sometimes a freer one, changed conventions and a greater tolerance towards ever-changing needs. But there is, against the picture of this changing life, the great constant of climate.”

St. Thomas' Preparatory School, Colombo, 1957–1963

Students of St. Thomas’ Preparatory School reportedly enjoyed the frequent rainy-day holidays occasioned by the flat-roofed structure of their classrooms shown in the drawings presented here. Its unsuitability to the environment led to repeated renovations, with multiple elements replaced over time, as shown in the colour photographs by Sebastian Posingis of the buildings in their present-day state. The murals and reliefs are by Ena de Silva’s son, Anil Gamini Jayasuriya. Ulrik Plesner is pictured here in one of Bawa's black and white photographs.

Author unknown

St. Thomas' Preparatory School, proposed classrooms, c. 1958

St. Thomas' Preparatory School, proposed classrooms, c. 1958

Geoffrey Bawa

St. Thomas' Preparatory School

St. Bridget's Montessori, Colombo, 1963–1964

Designed in a manner that “can be visually understood by any intelligent four-year olds”, to quote Bawa, the classrooms at St. Bridget's Montessori aim to create the impression of a shelter under a tree, with openings in the low walls proportionated for toddlers. The early section here looks at the wide pitched roof, while the final built iteration would include a monitor roof, its central portion lifted to allow for the escape of hot air.

Author unknown

St. Bridget's Montessori, elevation, c. 1963

Ink on tracing paper

St. Bridget's Montessori, section, c. 1963

Graphite on tracing paper

Graphite on tracing paper

Geoffrey Bawa

St. Bridget's Montessori, c. 1963

5 Gelatine silver prints

St. Bridget's Montessori, c. 1963

5 Gelatine silver prints

Steel Corporation Offices & Staff Housing, Oruwela, 1963–1968

Part of an impressive complex of buildings constructed for the state-owned Steel Corporation, this elegant administrative building was created with an overhanging upper floor which appeared to glide over the pond used by the steel mill. The reinforced concrete structure is buttressed to support the overhang, and precast concrete panels at varying scales are used as infill.

Author unknown (this drawing was likely made for the 1986 Mimar publication)

Steel Corporation Administrative Building, plan, section, and elevations c. 1986

“At random I take an isolated item, the — what is now called — Sinhala tile. The Arab traders introduced to Sri Lanka many centuries ago the half-round clay roofing tile of the Mediterranean world, but the roofs built in Sri Lanka with them were more steeply pitched to shed the huge rainfall of our country. The Portuguese and the Dutch used the same tile and roof pitch but the latter raised the roofs higher for coolness, with wide eaves and verandahs to shade the walls. In the hill country the Kandyans used a flat clay tile like a shingle on their double-pitched roofs in meeting halls which had only columns, no walls — an answer to a way of life — a great roof to give shade and shelter, open to the drift of air and the encompassing view. More than functional building it is first rational building, for it is rational to give presence to both function and form, to admit beauty and pleasure as well as purpose.”

Bentota Beach Hotel, Bentota, 1966–1969

One of the earliest and most influential resort buildings in Asia, the Bentota Beach Hotel featured highlights by many of the artistic collaborators who were intertwined with Bawa’s practice: the stunning batik ceiling by Ena de Silva, the brass peacock sculpture by Laki Senanayake, the metal doors and hand-drawn panels by Ismeth Raheem, and the vibrant sunset-hued textile ceiling by Barbara Sansoni. Its structural innovation is credited to Bawa’s partner at Edwards, Reid and Begg, the brilliant Dr. K. Poologasundram, whose shadow is pictured in his own photograph of the building.

Unknown author

Bentota Beach Hotel, section, c. 1969

Ink on tracing paper

Bentota Beach Hotel, section, c. 1969

Ink on tracing paper

Unknown author, based on original drawing by Anura Rathnavibushana

Bentota Beach Hotel, site plan, c. 1969

Bromide print

Bentota Beach Hotel, site plan, c. 1969

Bromide print

State Mortgage Bank (later Mahaweli Office Building), Colombo, 1971–1978

The early plan of the State Mortgage Building, laced with windows along its perimeter, shows the intention to naturally ventilate the twelve-storey building from the project’s onset. The section of the wall shown here reflects an evolved design that relies on windows at two heights to bring in cool air and send out the heat. The air circulation is drawn so dynamically that its movement can almost be felt.

Author unknown,

State Mortgage Bank, plan of typical office floor, c. 1971–1978

Ink on vellum

State Mortgage Bank, plan of typical office floor, c. 1971–1978

Ink on vellum

Author unknown,

State Mortgage Bank, detail section of windows, c. 1971–1978

Diazotype

State Mortgage Bank, detail section of windows, c. 1971–1978

Diazotype